In response to my recent post, Concerns about the legitimacy and integrity of Nucleus Genomics, Stephan Cordogan, the lead author of Nucleus Origin, posted a response, entitled Setting the Record Straight on Nucleus Origin (Twitter/X post here, archival PDF here).

Table of Contents

Addressing the least of their sins

Stephan’s post is a fairly directed, technical response to certain methodological critiques of Nucleus Origin. First, I think it’s interesting that Nucleus chose to elide any discussion of:

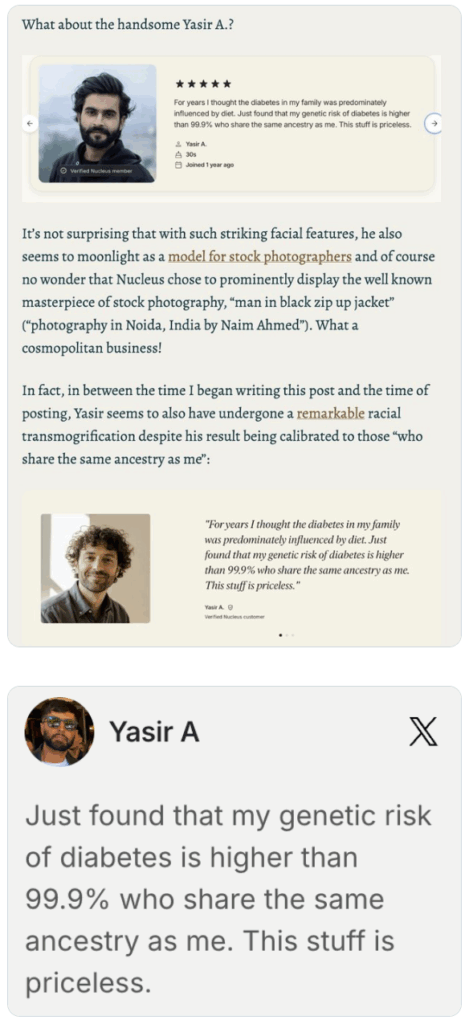

- Their fake/AI-generated reviews and impossible timelines for the birth of embryo-selected babies (amusingly, their race-shifting Yasir seems to have undergone yet another transformation in the last day or two).

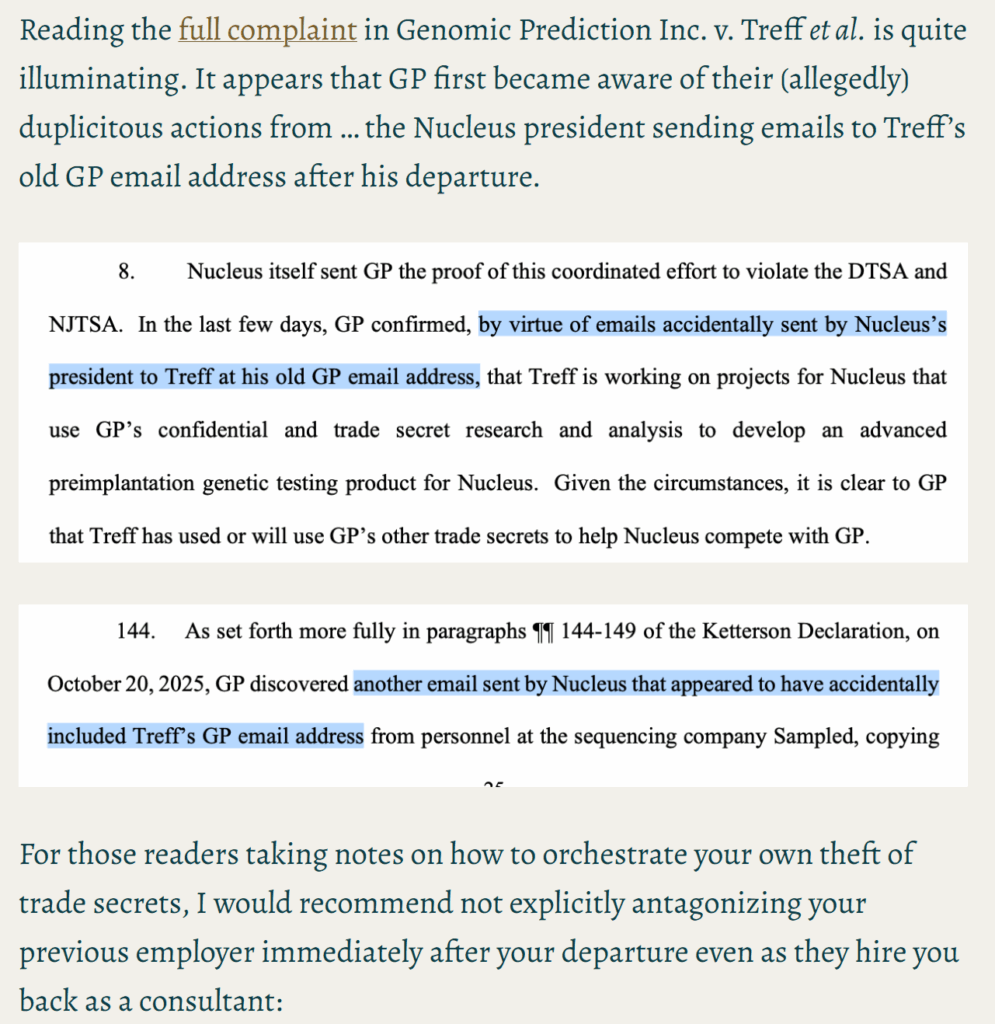

- Intellectual property theft allegations (besides a tweet from the founder crowing about how the preliminary injunction GP initially requested was denied, notwithstanding the fact that this constitutes no conclusion about the merits of the case).

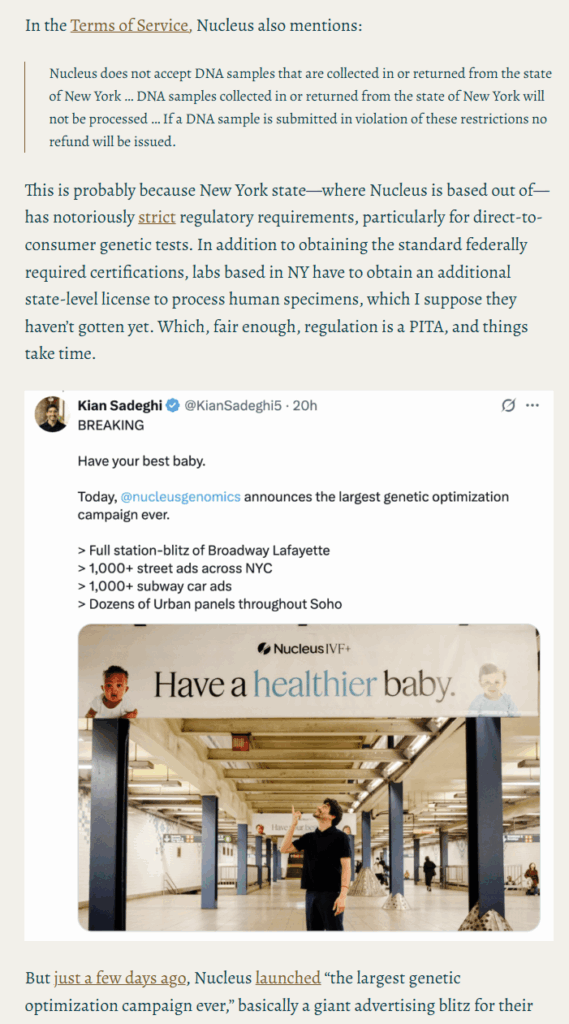

- Why they are releasing a blitz of ads in NYC when their ToS explicitly forbids New Yorkers from using their product likely due to regulatory reasons.

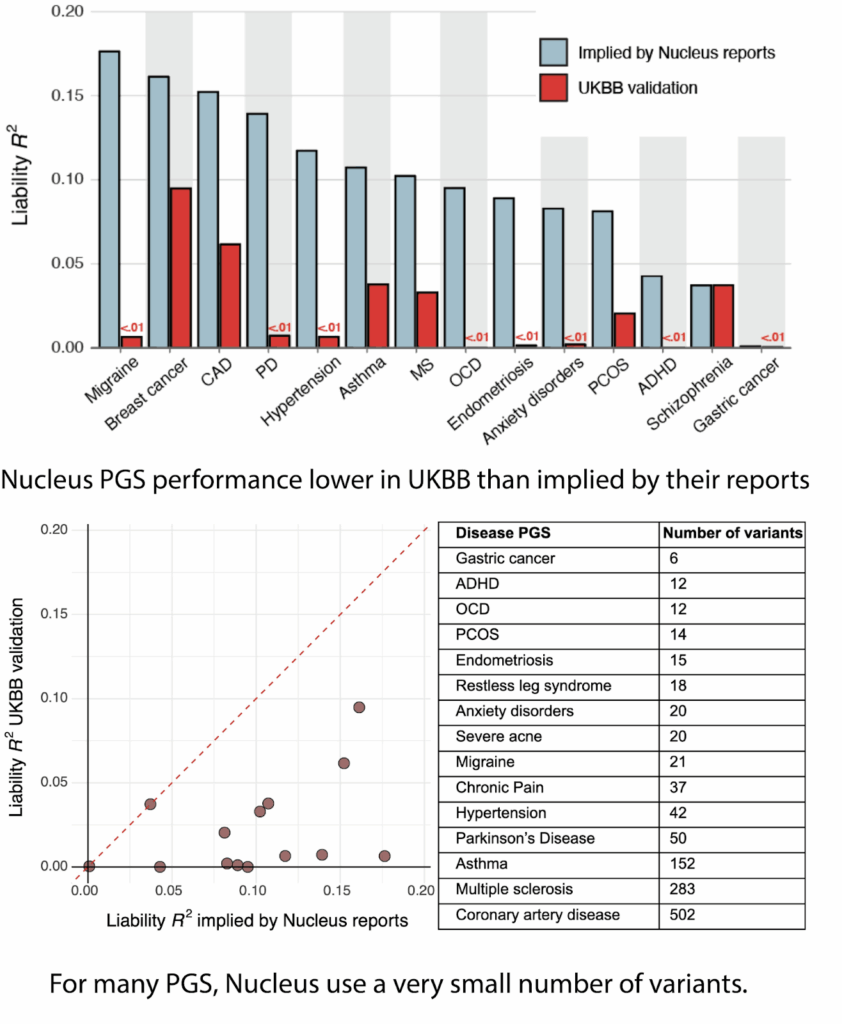

- Their documented history of falsifying performance metrics (see e.g., Scott Alexander’s post).

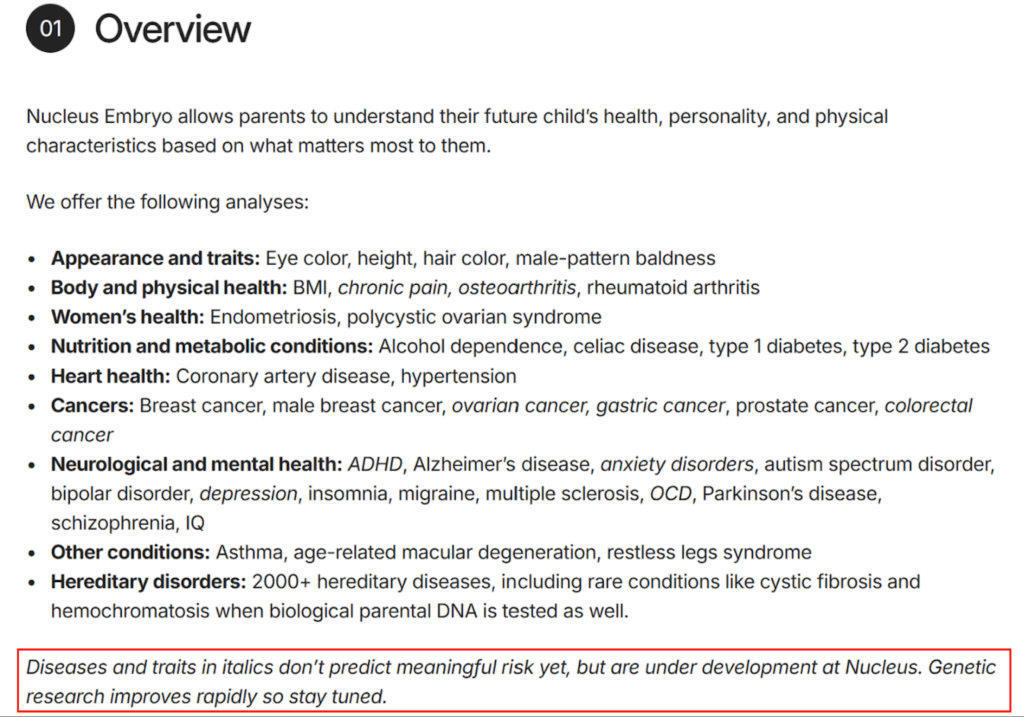

Actually, it appears that they now essentially concede the last point. Looking at their website, they now state:

Besides the fact that only 9 of these diseases are covered in their Origin whitepaper, I’m not entirely certain what it means to offer a trait that uses a score which does not “predict meaningful risk yet,” especially given that all of these traits are listed as part of their actual offerings on their “what’s included” page. After all, couldn’t one offer any trait if there’s no requirement that it actually predicts anything meaningful? As far as I can tell, based on descriptions of users’ physicians’ reports and customer testimonials, risk predictions for the italicized diseases have in fact been included in reports in the year prior. Moreover, it is quite suspicious that the italicised traits overlap significantly with the traits that in Scott’s blogpost which showed the worst discrepancies between claimed and actual performance:

But leaving these points aside, their overall approach to communications is understandable —given that the whitepaper is the only concrete artifact Nucleus has produced, it is in a sense the easiest to directly defend, as well as the most difficult to follow for non-experts. In any case, I understand if it takes some time to figure out how exactly you want to justify pushing out AI slop, and in the meantime I’m more than pleased to engage in a dialogue about the technical merits of my critique.

A reminder of their core claims

However, before I respond point-by-point, I want to appropriately frame this discussion and remind the reader of how Nucleus continues to describe their Origin product (emphasis mine):

We’ve had a breakthrough in applying AI to genetic analysis.

Origin is a family of nine genetic optimization models that predict human longevity from an embryo’s DNA more accurately than any genetic model to date.

Trained and validated on data from millions of individuals, Origin sets new accuracy benchmarks for predicting age-related conditions such as heart disease and cancers across diverse ancestries.

They are not just saying: “Here’s a standard product that we built using best practices from the academic literature.” Instead, they are claiming they have a “breakthrough in applying AI” that results in “new accuracy benchmarks.” Nucleus is making specific claims of novelty and technical superiority in marketing materials that are meant to directly inform potential parents of the merits of their Origin platform.

In Stephan’s response, there are two fundamental sources of argumentative tension:

- The first is that if Origin heavily utilizes “standard industry practices,” and that all similarities with Herasight boil down to usage of best-practices techniques, then Origin is straightforwardly not a breakthrough and lacks scientific novelty.

- The second is that Stephan claims that my “substantive technical claims are false” yet in 2/7 of his criticisms he admits that the whitepaper was incorrectly written and in another 1/7 he admits that the technique used is nonstandard and lacks prior justification. It actually seems like the one making false technical claims is Nucleus, not me.

I recommend that the reader keep these in mind throughout my response.

With that said, let’s dive right in.

Response 1: Nucleus admits that Origin is not novel

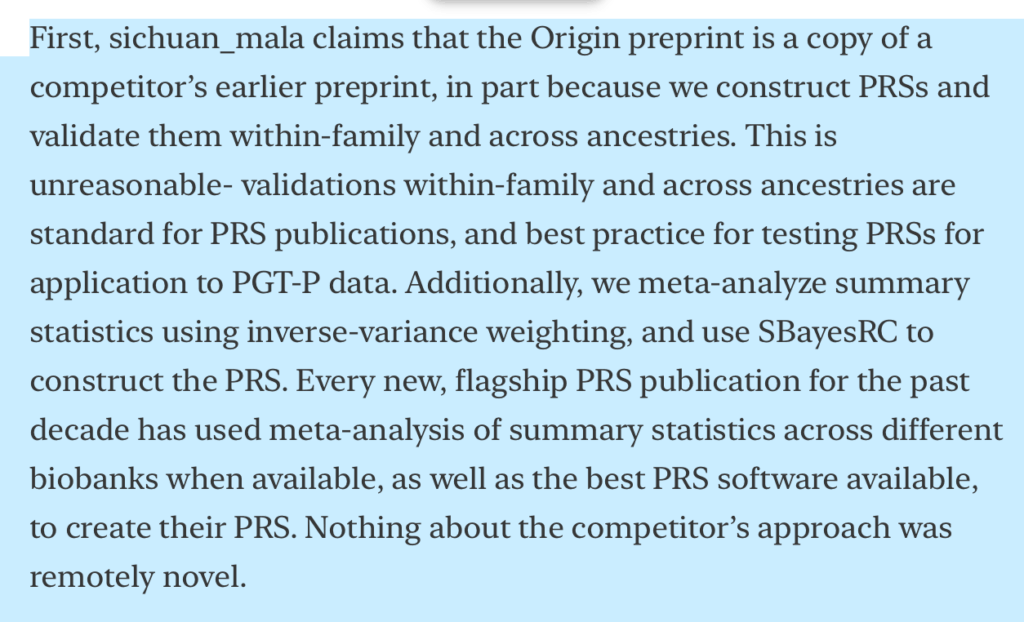

In my original article, I argued that the Nucleus and Herasight papers appeared suspiciously similar in part due to their usage of “identical polygenic score construction methods.” In response, Stephan argues:

This is a really interesting way to respond to my article, because if Stephan had read my article carefully, he would have noticed that I explicitly say, “of course, maybe given the state of the field there’s just one best way to perform this calculation and no good reason to deviate from this procedure.” Indeed, there’s no reason to reinvent the wheel just for the sake of novelty! However, pay attention to the very next sentence of my critique:

However, when you apply a known method in the exact same way that a competing company did several months ago, that simply does not constitute a ‘breakthrough.’

Curiously, Stephan actually agrees with me here. He explicitly claims that nothing about Herasight’s approach was “remotely novel.” Additionally, Stephan seems to agree that the exact same PRS analysis methodology was used by both Nucleus and by Herasight.

Therefore, is Stephan not himself arguing that Nucleus Origin is not, as they claim, “a breakthrough in applying AI to genetic analysis?”

Exactly what level of similarity constitutes plagiarism is not well-defined, and I’m happy to leave that judgment to the reader. In my prior article, I explicitly say that the similarities should be “taken in aggregate” when it comes to a determination of plagiarism. However, it is funny to me that the very first response made in Stephan’s article… actually explicitly supports my argument!

Interestingly, in the process of drafting this response, I took a quick look at the state-of-the-art methods for constructing polygenic scores, and it was nearly immediately evident that, even on purely technical grounds, there simply is no “best PRS software available.” SBayesRC is one strong option, but it is merely one of many competing state-of-the-art approaches released in the last 1–2 years. Just glancing at papers which cite SBayesRC on Google Scholar, we immediately notice a number of new methods, such as VIPRS, PGSFusion, PUMAS-SL, and OmniPRS, all of which report improvements over earlier pipelines in at least some settings, and some of which explicitly compare themselves to SBayesRC.

For example, PRSFNN—released months before Origin was announced and with fully public code—claims substantial performance gains over SBayesRC on several complex traits. In other words, by the time Nucleus decided to build Origin, the choice to center everything on SBayesRC was made in a landscape where multiple, potentially stronger alternatives already existed.

Let’s summarize what we’ve learned here. First, Nucleus basically admits that they followed the exact same PRS construction methodology as the Herasight paper, implying that their own Origin product is not remotely novel. Second, considering that they relied on exactly the same method (SBayesRC) as a close competitor in an arguably rushed paper published in pretty much the exact timeframe you would need to replicate their work and in the presence of multiple other valid alternative choices (PRSFNN, etc.) therefore still remains suspicious and indicative of plagiarism.

Can you believe we’re only at response 1 out of 7?

Response 2: Nucleus continues to make false performance claims

In my original article, I pointed out that Nucleus compared their liability R2 values to the same literature references that the Herasight whitepaper did, with suspicious similarities in plotting style. I also pointed out that they made unjustified claims about the superiority of their Origin polygenic scores, and finally that they omitted any description of how they translated European lifetime disease prevalences into ancestry-specific values.

There are a number of intertwined points here, so let’s carefully go through them step-by-step.

Nucleus’s score performances do not “predict human longevity … more accurately than any genetic model to date” or “set new accuracy benchmarks”

First, Stephan writes:

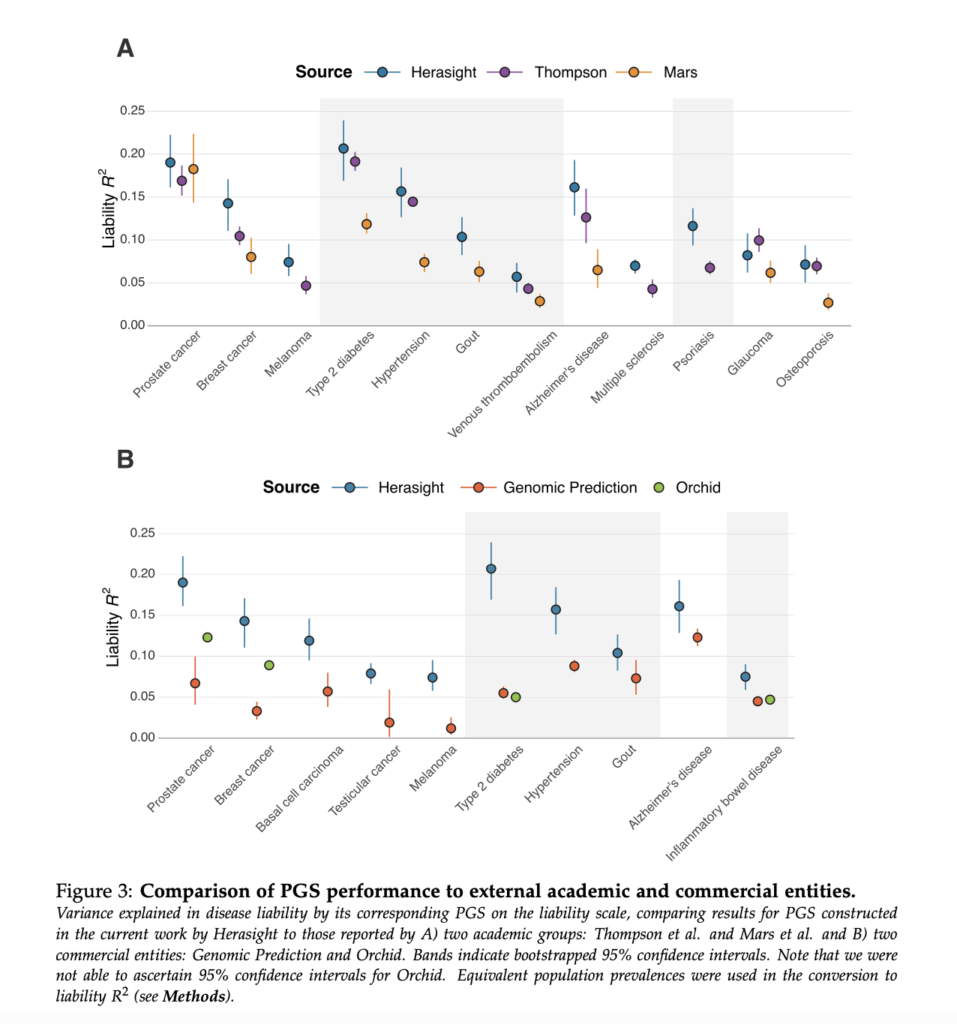

For reference, let’s also take a look at the plots in question.

From the Nucleus whitepaper:

From the Herasight whitepaper:

To start with, it’s true that it’s not in and of itself unreasonable to make comparisons to the same literature references. And whether or not the visual similarities are great enough that they contribute to the “aggregate” of overall similarities is a judgment call that I’m happy to leave up to the reader.

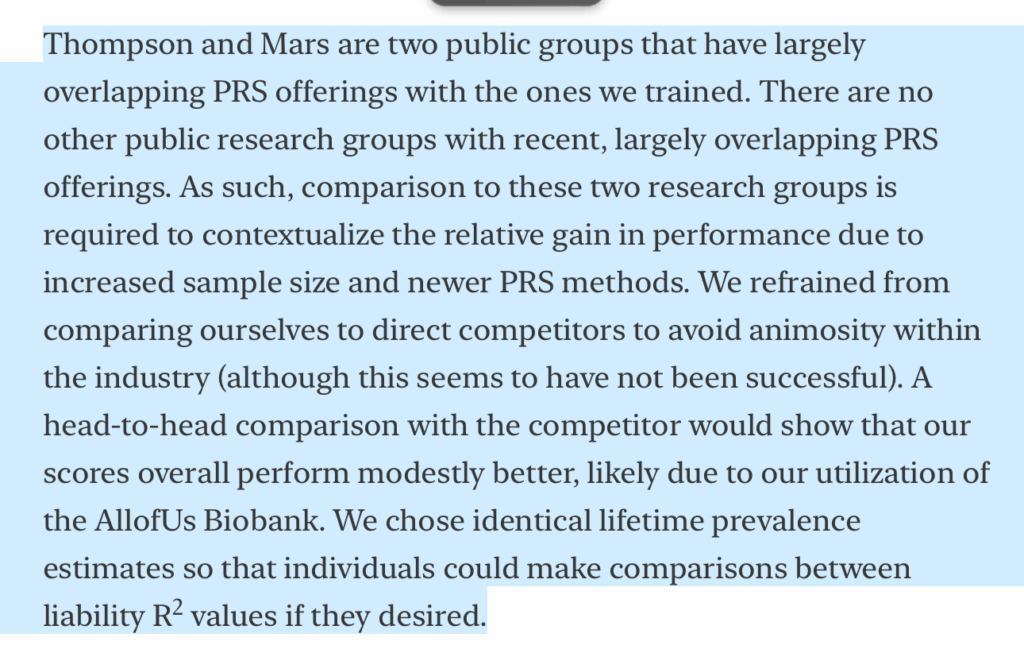

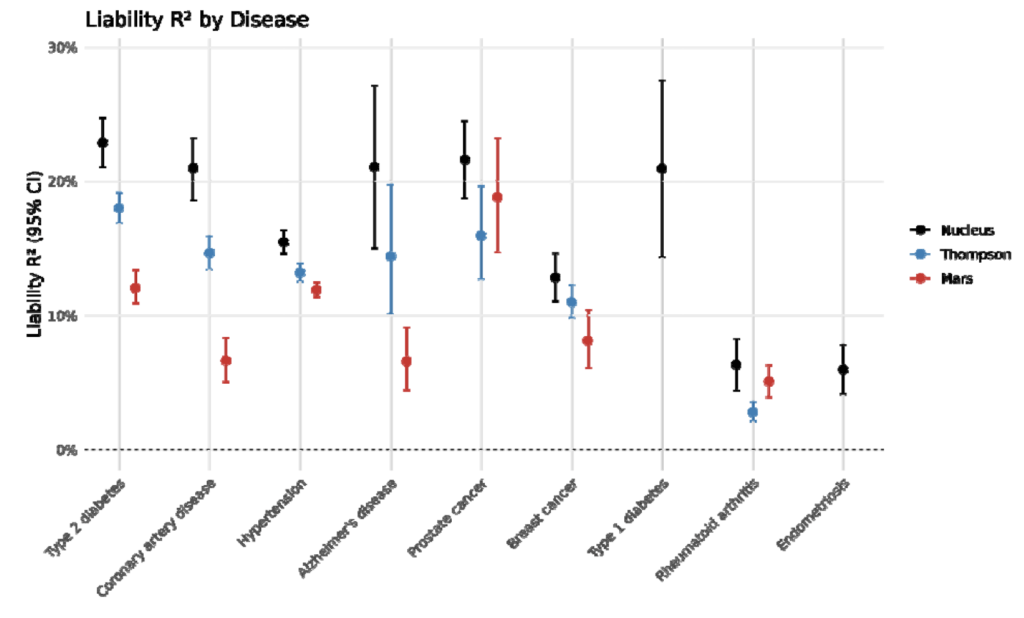

However, it’s really interesting that Stephan claims that they “refrained from comparing ourselves to direct competitors to avoid animosity.” Remember that on the front page of Nucleus Origin, they wrote that Origin “predict[s] human longevity … more accurately than any genetic model to date.” This is not only a totally unsupported claim, given that none of the results above directly pertain to longevity, but also a direct statement that Origin’s product is superior to those of competitors. Similarly so with their claim that Origin “sets new accuracy benchmarks.” It seems that Nucleus is in fact very interested in drawing comparisons with direct competitors!

It is also at least questionable for Nucleus to claim that the exact same two papers that Herasight used in their own benchmarking are the only recent works to compare themselves to. For instance, what about the recent large-scale PRS evaluation in Lerga-Jaso et al. (2025), published in May 2025, which compares multiple architectures and provides AUC estimates across many of the same diseases? Given that I’m a layman in this field, if I could find this paper in the time it took me to draft this response, presumably Nucleus should have been able to do so as well in the Origin development process. The fact that Nucleus instead chose to reproduce the exact same pair of comparisons used by Herasight strongly suggests that the visual similarity of the figures is no accident. It is much closer to a template being reused than to an independent evaluation designed to support claims of novelty or technical superiority.

Let’s finally turn to Stephan’s claim that “head-to-head comparison with the competitor would show that our scores overall perform modestly better.” This is … simply untrue? Taking the liability R2 metrics at face value (Table 2 in their whitepaper), Nucleus Origin seems to slightly outperform Herasight in some diseases (e.g., prostate cancer or type 2 diabetes), and Herasight (Supplementary Table 2 in their whitepaper) seems to slightly outperform Nucleus Origin in some other diseases (e.g., hypertension or breast cancer). Also, Herasight’s paper contained more scores, so it’s not actually possible to do a full head-to-head comparison in the first place.

To summarize, Nucleus Origin clearly does not have “state-of-the-art prediction” that “surpasses all published accuracy benchmarks.” In fact, it’s actually confusing to me why they keep making this claim even when it’s so trivially disprovable. On top of that, Stephan’s defense of their choice of literature comparisons is hilarious—similarly with his earlier defense of SBayesRC, the Nucleus response actually prompted me to find even more reasons why the similarities with the Herasight paper are indicative of plagiarism!

Nucleus’s prevalences are clearly directly copied from Herasight’s preprint

A related and far more important point that Stephan’s response accidentally highlights is the way in which Origin handles lifetime disease prevalence. In my original post, I mostly complained about the missing details for non‑European prevalences. But if you look more closely at their European lifetime prevalences, something even more striking appears.

Herasight’s preprint assembled lifetime-risk estimates from a rather wide array of sources. This curation (including sources) is documented in their Methods section and the Supplementary Tables.

Origin’s Table 2 reproduces these numbers exactly. For the five overlapping diseases (Alzheimer’s, breast cancer, hypertension, prostate cancer, and type 2 diabetes), Origin’s overall prevalence values match Herasight’s values when averaged over the latter’s sex-specific prevalences, digit-for-digit:

- Alzheimer’s disease: 11.1% (the mean of Herasight’s 8.8% male / 13.4% female)

- Hypertension: 46.85% (the mean of 45.40% and 48.30%)

- Type 2 diabetes: 19.9% (the mean of 21.40% and 18.40%)

- Breast and prostate cancer: identical to Herasight’s SEER-based values

Origin even reproduces Herasight’s highly specific choice of using FinnGen Risteys I9_HYPTENSESS as the source for hypertension lifetime risk, which seems to me to be far from an obvious first choice. Yet Origin does not cite FinnGen Risteys anywhere in their Methods (nor any of the other sources Herasight lists for their prevalence estimates). Nor do they provide any explanation for how they arrived at the exact same numbers.

Their Methods instead wave this away with a vague description about “deriving lifetime prevalences from the literature.” That claim does not withstand even superficial scrutiny, because no combination of commonly cited sources produces these specific figures unless one follows the exact decisions made in Herasight’s curation.

And indeed, in Stephan’s Substack response, he openly admits that Nucleus “chose identical lifetime prevalence estimates so that individuals could make comparisons between liability R² values,” which is simply an admission that they reused Herasight’s numbers outright.

Of course, scientific groups can use the same sources. But copying a competitor’s curation without citation of either the competitor’s work or the original data sources, and then presenting it as your own work, is not “standard practice.” It is the textbook definition of uncredited reuse. Taken together, this supports exactly the point I made in the original post: the similarities between Nucleus’s and Herasight’s whitepapers are not coincidences—they are evidence of a whitepaper assembled by copying the work of others and filling in the gaps after the fact.

In the end, Stephan does respond to my original complaint by providing some additional detail on their calculation of ancestry-specific lifetime disease prevalences. As I noted in my original post, the omission of detail is “representative of a broader trend in the paper where critical details about methodology, often required for proper interpretation of the results they present, are just totally absent.” I continue to stand by that assertion. It’s ridiculous that a basic arithmetic formula is supplied not in the whitepaper but instead in a Substack response to an anonymous blogger’s critique.

The statement “data available upon reasonable request” has been a meme in the academic sphere for some time. Perhaps Nucleus is also innovating here with a new approach: “methods available upon reasonable request.”

Response 3: Upon further investigation, Nucleus’s identical citation appears even more suspicious

Here, I actually have to thank Stephan for prompting me to look a little deeper into the similarities between the Nucleus and Herasight whitepapers, which has helped me come up with even more circumstantial evidence to support my original post.

Recall that I originally argued that both the Nucleus and the Herasight whitepapers “reference the exact same 2025 paper from Tucker-Drob in the quality control step,” with oddly similar wording in the methods section of both papers. Again, as with the construction of the polygenic scores, I’m not saying that I’ve dispositively proven plagiarism, but that the similarities, when “taken in aggregate,” are highly suspicious.

Stephan argues:

First, I already wrote in my original post that perhaps “one could argue that perhaps Tucker-Drob (2025) is simply the right way to perform this step of the analysis,” but then immediately after noted that a surprisingly small number of papers reference Tucker-Drob (2025). In combination with the similarities in wording (“following … recommendations from Tucker-Drob (2025)”), I argued that this supports the charge of plagiarism.

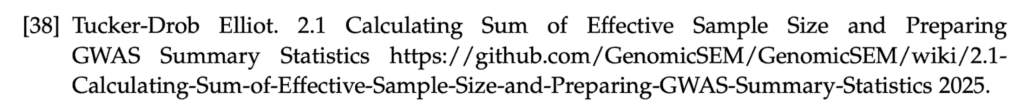

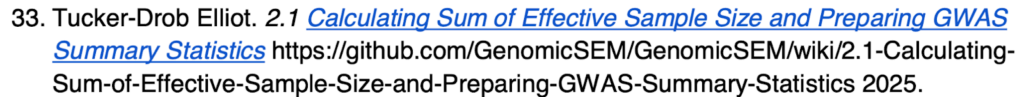

Some of that is maybe a subjective judgment call. However, interestingly, I decided to look at the two whitepapers again, and they actually use the same citation, word-for-word, for Tucker-Drob (2025). Compare:

And:

Maybe their citation formatter happened to spit out the citation for this particular reference, despite the rest of their bibliographies clearly using different reference formats? However, that’s not all! If we follow the link, it turns out that, as Stephan helpfully notes, it’s just a page on the GenomicsSEM GitHub wiki. The revision history of this wiki goes back to March 2022, and the methodology on this page was introduced by Grotzinger et al. (2023), published in January of that year.

Logically, if this method is really so commonly cited in the genomics literature, we should be able to find some other papers that reference section 2.1 of the GenomicsSEM GitHub wiki, especially considering it’s been around for over two full years, right? However, if we search the GitHub URL for that page on Google Scholar, we only find five results:

The 2nd result is the paper introducing the method described at that URL, the 4th result is the Nucleus whitepaper, and the 5th result is the Herasight whitepaper. Aside from these, there have only been two other papers that reference Tucker-Drob (2025), both with the same author, and both with a different citation style from the Nucleus/Herasight papers.

I agree with Stephan that “GenomicSEM is one of the most cited statistical genetics software packages, and Elliot Tucker-Drob is one of the most cited statistical geneticists.” In that case, it would be perfectly normal to have a citation to GenomicsSEM or to some random paper by Elliot Tucker-Drob. However, that’s not what happened; instead, they have an identically formatted reference to the same random part of the GenomicsSEM GitHub wiki page, used in the same way with very similar inline wording, and almost no other papers that I can find have ever cited the URL for this wiki page.

Is this plagiarism? Or a mere coincidence of colliding methodological choices? I invite the reader to draw their own conclusions.

Response 4: Nucleus fails at reading their competitor’s methods section

Again, Stephan’s response here mixes together several independent points, and it’s clearest to address them separately.

First, in my original article, I noted that according to the text of the Nucleus preprint, they appear to have trained on the test set. Stephan claims that this was a “typo” that “will be corrected.” I’m glad that this error was merely a typo, but it just points again to the absence of care and detail that went into producing the Origin whitepaper. If a healthcare company announces a flagship product with a whitepaper that has multiple obvious typos, I think consumers are right to be concerned about the actual quality of the product delivered!

Second, Stephan attempts to counterattack by claiming that Herasight’s paper uses shady methodology:

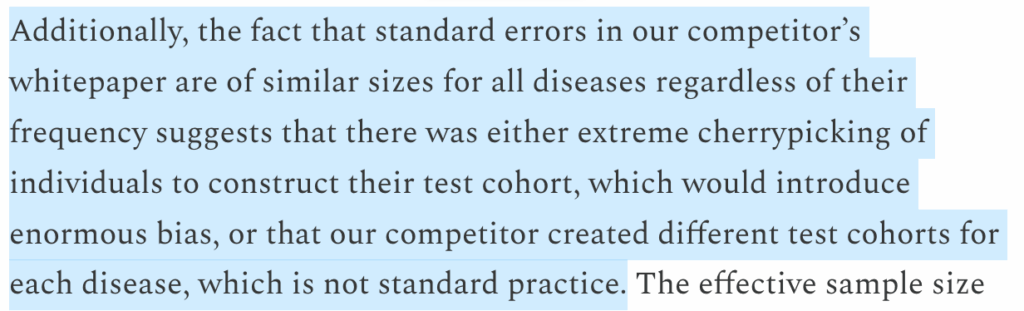

Well, I’m a little confused why he’s bothering to make this argument because you’ll recall that my prior article was titled “Concerns about … Nucleus Genomics” and not “Concerns about Herasight” but it took me approximately five minutes to figure out that the Herasight CIs are similar because they validate them in test sets of identical size:

You might disagree with the validity of this methodology, but considering that the exact method used is given two pages into the methods section with a bolded title, I wondered why Stephan thinks that Herasight “did not explain how their test cohorts were defined.” Most likely, the explanation is entirely prosaic; indeed, not reading Herasight’s preprint with sufficient care is evidence more of Stephan’s sloppiness than any imagined malfeasance.

Third, I made a technical criticism of the construction of their sibling validation set, and Stephan writes that “sichuan_mala’s claim about the non-independence between the sibling halves is valid, but this doesn’t bias the liability R2 estimates, only expands the confidence interval of the estimates slightly.” Upon further review, I’m happy to concede that this should theoretically only expand the standard errors; however, it’s not at all clear to me that the standard errors would only be expanded “slightly.” In any case, “this error doesn’t introduce bias, it just expands the standard errors” is still an admission that the error is correctly noted.

It looks like Nucleus copied Herasight’s within-family pipeline, but did so incorrectly

Interestingly, after taking a closer look at the Methods sections in the Nucleus and Herasight whitepapers, I noticed even more similarities between the two. Much like the exactly-copied European lifetime prevalences, the similarities this time are so exact as to leave almost no room for doubt.

Specifically, the within‑family pipeline Herasight uses consists of a probit mixed model, family random intercept, imputed parental PGS via snipar, and a bootstrap for the ratio of within‑family to population effects. This is not some generic, off‑the‑shelf recipe one can grab from any PRS tutorial, but instead clearly customized to their specific analytic preferences. Origin adopts an essentially identical approach, less the snipar imputation: same modelling framework, same attenuation ratio, same idea of bootstrapping the ratio. Even the software used is exactly the same (R package lme4)!

Even worse, their own description of the bootstrap is underspecified and appears potentially wrong: they just say “we obtained standard errors via 1000 bootstrap replicates,” with no indication that they resample at the family level. If they in fact resampled individuals rather than families, that would artificially shrink their standard errors and make the within‑family results look more precise than they really are because this doesn’t account for dependence between siblings. Had they actually provided methodological details, we would be able to confirm this one way or the other—as it stands, we’re stuck guessing.

Essentially, it appears that Nucleus plugged in a simpler, sibling-based linear model into Herasight’s generalized linear mixed modeling framework (identical down to the usage of a probit link function and the R package lme4). This framework, to the best of my understanding, has not been published anywhere else and is far from a standard set of literature techniques. Also, they may have messed up the bootstrap, although it’s hard to know for sure.

In summary, we’ve ended up in a slightly absurd position where Nucleus appears to have copied an unusual, non‑standard method from a competitor, might have failed to implement an important detail correctly, while again providing no citation for such, and also suggesting malfeasance on the part of Herasight due to their lead author’s own inability to read a paper with sufficient care.

Response 5: Nucleus seems to think that common practices are “unusual”

In my original post, I noticed that Nucleus identified 40,872 siblings of European ancestry in the UK Biobank, which is significantly larger than the ~36k siblings identified by Young et al. (2022). Stephan’s response is essentially that other analyses have also identified ~40k European siblings in the UK Biobank:

While superficially compelling, Stephan’s response is actually sloppy and confused.

For example, his citation [5] is to Lello et al. (2023), Sibling variation in polygenic traits and DNA recombination mapping with UK Biobank and IVF family data. This paper constructs their cohort using “sibling pairs of self-reported European (White, in UKB terminology) ancestry,” whereas the Nucleus whitepaper “defined Europeans as individuals who were both genetically predicted to be European and reported only European ancestry,” meaning that Lello et al. is using a more permissive criterion for European ancestry than the Nucleus whitepaper. The fact that they identify similar numbers of siblings is actually a point against the correctness of the Nucleus whitepaper.

Taking a look at the literature, we can readily find more papers that disagree with Nucleus on how many White European sibling pairs exist in the UK Biobank data, though. For example, Kemper et al. (2021), Phenotypic covariance across the entire spectrum of relatedness for 86 billion pairs of individuals identified “20,342 pairs consisting of 36,920 individuals in our British and Western European dataset.” Similarly, Markel et al. (2025), Nature, nurture, and socioeconomic outcomes: New evidence from sib pairs and molecular genetic data identify 18,949 European sibling pairs in the data; multiplying by two, we arrive at an upper bound of 37,898 individuals. It remains unclear exactly how Nucleus arrived at their count of ~40k siblings.

Stephan then counterattacks by claiming that Herasight’s “unusual choice to restrict their analysis to self-reported Caucasian/White British apparently decreased the size of their sibling cohort to 35,197.” Again, it’s not clear why a potential error in Herasight’s paper has any bearing on the accuracy of a post titled “Criticisms of … Nucleus Genomics.” However, Stephan’s criticism is also straightforwardly wrong on multiple levels.

First, the Herasight whitepaper clearly uses the standard UK Biobank White British ancestry subset which is based on a combination of self-reported ancestry and genetic clustering analyses, so Stephan’s description of their methodology, and his claim that it’s an “unusual choice,” are both wrong. Second, the Herasight analysis doesn’t just use sibling pairs, so the number of probands identified is not directly comparable. Third, the number that Stephan quotes—35,197—literally does not appear anywhere in the Herasight preprint. It does appear in Young et al. (2022), which I screenshotted in my original post, but that has no direct relation to Herasight’s whitepaper, and is also defined using the standard UKB subset I described above.

To elaborate further, Herasight appears to have restricted analyses to individuals with self-reported ancestry that is consistent with their inferred genetic ancestry (as officially defined in UK Biobank Field 22006), a subset which seems to be so commonly used that even the official UK Biobank paper on the release of their Whole-Genome Sequence data acknowledges it as the basis for “many GWAS.” In fact, even Nucleus’s own CSO Lasse Folkersen coauthored a paper that restricted “to the “White British” group defined by the UK Biobank (Field 22006) to “get a set of genetically homogeneous individuals.” Therefore, it’s quite confusing why Stephan believes that the Herasight whitepaper’s ancestry filtering is “unusual.”

Response 6: Nucleus still fails to justify “total blood pressure” as a diagnostic criterion for hypertension classification

In my original article, I pointed out that Nucleus uses a weird definition of hypertension, where they sum systolic and diastolic blood pressure into “total blood pressure,” add some constants to adjust for medication usage, and check if the resulting value is greater than 230 mm Hg. I claimed that this is a nonstandard procedure, and I continue to stand by that claim.

Stephan writes:

I will from the outset agree that offsetting blood pressure for medication usage is standard practice. In my original article, all I wrote about the offset is that “it’s not clear where they got … this from.” That remains true of their whitepaper, and it would have been great if they had added the appropriate citations!

As with my original post, I take greater issue with the definition of “total blood pressure.” Yes, obviously, if you sum two highly correlated traits with overlapping causal factors, you should be able to generate a superior predictor for the summed trait rather than for each trait individually.

This does not change the fact that hypertension is not defined as such, but as systolic blood pressure exceeding 130 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure exceeding 80 mm Hg. (Exact definitions could perhaps vary, but the point is that you have to look at both systolic and diastolic figures).

If you use a non-standard definition of hypertension to train and evaluate your polygenic scores, how exactly are we supposed to interpret or evaluate your results, both in absolute terms and in comparison to others? In principle, they could make an argument that their usage of “total blood pressure” somehow produces superior results, or that the standard clinical definition of the disease should be changed. I’m not saying that such an argument can’t exist. Instead, I’m just pointing out that they made an objectively bizarre methodological choice with zero justification.

Response 7: Nucleus admits they made “typos”

In my original article, I pointed out that the Origin whitepaper appeared to use incorrect ICD codes for their definition of prostate cancer as well as incorrect UK Biobank codes for their definition of rheumatoid arthritis and type 1 diabetes.

Stephan writes:

Great to hear that it was just a “typo.”

While this is a valid response to my criticism, it is still an admission that their whitepaper included errors. As I wrote in my original article, “even a cursory pre-publication review of this article would have trivially caught this error (or just ask ChatGPT?).” At the risk of sounding like a broken record, if Nucleus can’t even check a major product release for basic typos, do you trust them to play a role in the birth of your future child?

Closing technical remarks

Let’s summarize what we’ve learned over the course of this back-and-forth:

- The lead author of Nucleus Origin admits that Origin is not novel and certainly not a “breakthrough,” and their CSO agrees that they simply used a “method developed by researchers at the University of Queensland.”

- Origin does not consistently outperform Herasight and does not “set new accuracy benchmarks.”

- The evidence for plagiarism is even worse than I originally thought:

- The Tucker-Drob citation is letter-for-letter identical to the Herasight citation.

- Stephan directly admits to copying the Herasight prevalence values digit-for-digit while neglecting to cite either the Herasight preprint or the original data sources.

- Nucleus uses, without attribution, the exact same non-standard generalized mixed model setup and exact same software as Herasight to calculate within-family prediction ratios. This method is not found anywhere in the literature aside from Herasight’s publication.

- Overall, the Origin paper uses a very similar structure, identical PRS construction methods, identical comparisons to literature, similar plots, identical disease prevalences for overlapping diseases, and the same non-standard setup for within-family analyses with only minor methodological differences across the entire paper. At no point is the Herasight whitepaper cited or acknowledged.

- Nucleus’s whitepaper includes obvious typos and unjustified methodological choices.

What’s most interesting is that in his response to my article, Stephan actually happily conceded most of these points himself, and for those he didn’t, he practically led me directly to them!

Quite a few errors were dismissed by Stephan as “typos.” I’m happy to accept that these reflect real typos rather than severe errors in the underlying analysis. However, combined with the presence of extreme similarities between the Nucleus and Herasight whitepapers—which I identified even more of in the process of drafting this response—the overall gestalt is supportive of the idea that the Origin whitepaper was hastily plagiarized from Herasight in an attempt to mount a competitive response. This is in addition to the lawsuit filed against them by Genomic Prediction alleging theft of trade secrets and confidential information, which, well, on one hand, the allegations remain unproven in court, but on the other hand, it’s not like facing IP theft lawsuits is an everyday occurrence for typical startups.

Again, let me emphasize that Nucleus went from claiming that Origin is a “breakthrough in applying AI” to, in their response, explicitly pointing out that the Origin whitepaper does little more than follow standard, well-known techniques from the literature (that just happen to be the same as those in Herasight’s white paper, and when they do veer off the beaten track, they also do so in the exact same way as Herasight). Maybe it’s just me, but this just reeks of a desperate attempt at damage control.

The larger, more concerning ethical points remain unaddressed

Let’s not forget that there are an enormous number of unaddressed points that I raised in my original article. Why does Nucleus post customer testimonials with stock or AI-generated photography? Why did Nucleus tell Scott Alexander to stop asking questions when he tried to dig into their performance metrics? Why do they offer screening using scores that “[do not] “predict meaningful risk” and that are not present in their Origin paper? Why did Nucleus launch an advertising spree in New York when their Terms of Service prevent them from serving NY-based customers? Why is Nucleus currently being sued by a competitor for theft of intellectual property? If this is all Nucleus can say in response, then I’m disappointed.

And frankly, the overall shape of their response makes the pattern even more obvious. Instead of addressing these genuinely disturbing issues, Nucleus fixates on narrow, technical quibbles. Their response reads less like an honest scientific rebuttal and more like an attempt to change the subject toward the one area where they think they can at least imitate competence.

That their CSO is now publicly doubling down on this strategy—portraying all criticism as mere “typos” in his supplementary tables and framing legitimate scrutiny as an attack from “the IQ-genetics crowd”—only underscores the point. Indeed, it is ironic for a company plastering the NYC subway with advertisements saying “IQ is 50% genetic” and offering IQ prediction for adults and embryos to sneer at the “IQ-genetics crowd,” just as it is for the same company to at once boast about how they have achieved an “AI breakthrough” while acknowledging that the way they achieved that very same “breakthrough” was not “remotely novel.”

I don’t want to sound like a broken record, but this exchange really doesn’t paint a picture of a competent, scientifically honest company. Again, this is a company that you’re supposed to entrust with choosing which embryo will become your future child.

Nucleus’s overall conduct thus far—repeatedly making extremely bold, unsupported claims, only to walk them back immediately (and in the case of the inflated performance metrics,1 silently) upon scrutiny, while impulsively levying serious and unfounded claims of financial conflicts of interest and suggestions of sinister conspiracies funded by unnamed competitors (archival screenshot)—is emphatically not commensurate with the behavior of a company which operates in good-faith and conforms with generally accepted ethical guidelines. These are serious matters with serious consequences, and well-meaning parents who invest their time and money into trying to prevent hereditary disease and providing the best possible life for their future child do not deserve the pattern of duplicitous behavior and flippant attitude with which Nucleus has treated, or ignored, the concerns I raised in my original post.

I believe that IVF and embryo selection technologies have immense potential to benefit mankind, and that’s exactly why it is so deeply upsetting to see Nucleus engaging in unethical marketing practices and sloppy science in service of customer acquisition. Everyone at Nucleus, including Stephan, should be ashamed of themselves for giving cover to sloppy plagiarism and potentially ruining the entire IVF-ART field for everyone.

P.S. To be painfully clear: I have no current or past financial interest in any embryo selection company, nor have I been compensated in any way for my tweets or posts.

Footnotes

1 It’s actually worse than just inflated performance metrics; the fundamental problem with the original offering is that risk predictions were calibrated to inflated performance metrics, meaning that they were telling people they had highly elevated/deflated risks of various diseases when they didn’t.

Leave a Reply